“Fascination and Enigma – Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi”

Text and translation by Claire Challancin

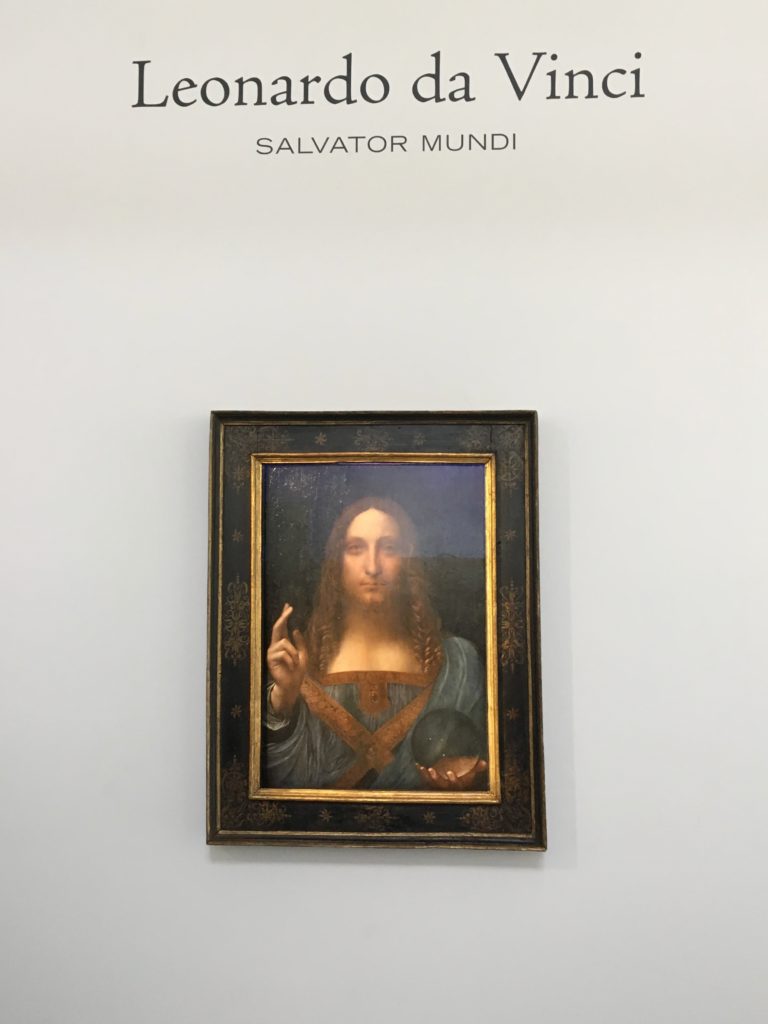

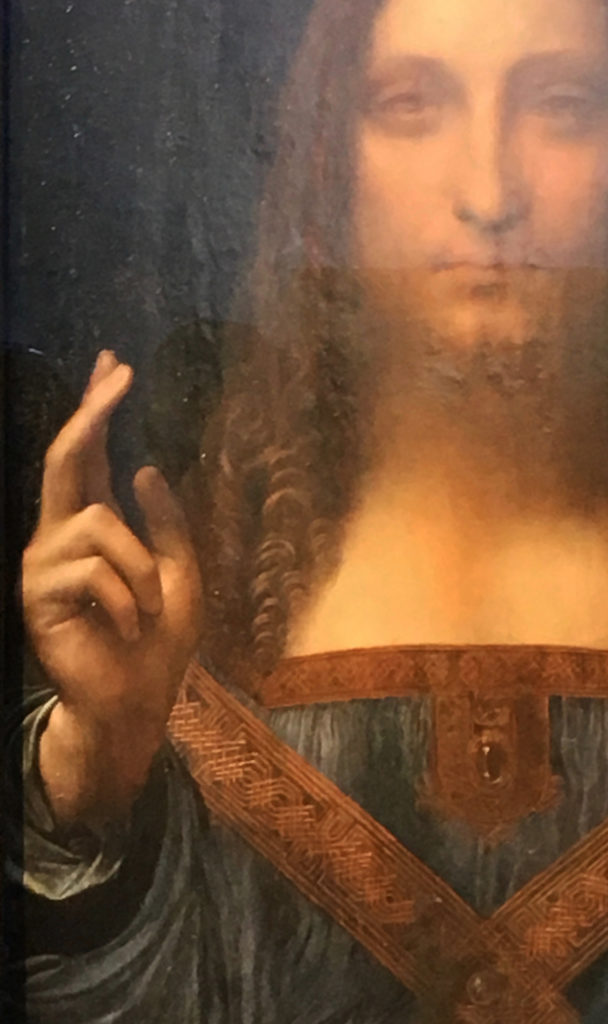

One of the greatest artists of all times, if not the greatest – Leonardo da Vinci – has left us no more than 30 paintings, testimonies of his artistic genius and talent. Milestones of the history of art and symbols of Renaissance, the Tuscan artist’s paintings fascinate experts and art lovers still today. Enigmatic and rich in symbols, his works have been thoroughly studied in the past decades by a great number of scholars, who have given a wide variety of different interpretations. Exactly because of the standing and prestige of this artist and his artistic production, the discovery, or rather the rediscovery, of one of his works has produced great interest and disarray among experts and art historians all over the globe. The reason of this confusion is the painting “Salvator Mundi” – Saviour of the World, a 25.8×17.9 inches oil on walnut, that after a ‘tour’ of few weeks will be sold at an auction in New York City, organized by Christie’s, one of the most important auction houses in the world. As it can be inferred from the title of the painting, the work portrays the figure of Christ blessing the viewer. Indeed, the subject is presented with his right hand and fingers pointing up, while the left hand holds a crystal globe illuminated by bright points, representing the celestial sphere and the stars. (Pictures 2, 3) In 2011, after having been exposed to scientific studies and to the analysis of four of the most important and influential experts of Leonardo’s production in the world, the painting has been verified as Leonardo’s original work. The following year Salvator Mundi has been shown at the exhibition organized by the National Gallery “Leonardo da Vinci – Painter at the Court of Milan”. Right now the painting is being displayed in San Francisco. Facing a Pollock, and at the side of a Kandinsky and a Magritte, thus creating an interesting contrast between modern and contemporary art and Renaissance art, it is now exhibited for few days at the Minnesota Street Project art gallery. (Pictures 4, 5)

Salvator Mundi’s Odyssey

The history of this painting is fascinating and almost incredible. Commissioned by Louis XII king of France, Leonardo painted the Salvator Mundi between 1506 and 1513. After few years the painting ends up in the hands of king Charles I of England and subsequently in the ones of his successor, Charles II. It then becomes property of an indefinite number of British noblemen, until 1763, when it disappears from the records. A few decades later, Sir Francis Cook, an art collector, buys the painting. However, what the English nobleman does not know is that the painting is actually a Leonardo’s piece. Indeed, during the years the work had not been associated to Leonardo, but to the school of Milan, and sometimes to a Leonardo’s pupil. Yet, the painting disappears again from the records for more than 100 years. In 1958, Salvator Mundi is sold for 45 pounds by a seller absolutely unaware of the real value of the masterpiece. Some decades later, in 2005, a Louisiana consortium of art dealers and investors buys the work for $ 10.000, and sponsor a first restoration and study. Finally, in 2011 a team of experts and scholars declares the painting an authentic Leonardo work. Afterwards, the Russian magnate Dmitry Ryboloviev buys the work for $ 127.5 million. Right now the painting is on display in San Francisco by the auction house Christie’s that owns the masterpiece. The painting has been exhibited by the auction house in Hong Kong, and will be shown in London and eventually in New York City, where there will be an auction from a starting value of $ 100 million. If a private collector buys the painting, the public will unfortunately not have the opportunity to admire Leonardo’s masterpiece anymore.

Authenticity proofs

As previously stated, throughout the years the painting stops to be identified as a Leonardo’s production. Due to the relocations and changes in ownership, the painting lost its identity as a Leonardo work. Moreover, during the years layers of paint and varnish are added to the original; mustaches and beard are painted on the Christ, hiding Leonardo’s characteristic lines and strokes. Therefore, the work loses its original features and is most often discredited as a simple copy of the florentine artist’s original masterpiece. Yet, after a first restoration, the superficial layers of paint were removed, revealing anew the leonardian typical traits. More in-depth analyses of the work, conducted by the restorer Dianne Modestini, show a pentimento, which scholars consider strong evidence of the authenticity of works. Furthermore, the pigments, analyzed and compared to the ones of the Virgin of the Rocks, provide additional proof and assert Leonardo as the artist. In 2011 the National Gallery invited four of the most famous and influential art historians and critics – Carmen C. Bambach, Pietro Marani, Maria Teresa Fiorio e Martin Kemp – to decreet, or deny, the authenticity. Unanimously the four scholars claimed and added the Salvator Mundi into the list of Leonardo’s works, officially declaring it as one of the most important paintings in the world. Kemp has indeed said that although he has constant skepticism, and research for flaws pointing to the inauthenticity of the work, he has not been able to find any. Marani, on the contrary, argues how “the quality of the painting, the beautiful colors, the reds and blues […] exactly remind to the ones of the Last Supper” (translated from Corriere.it). Yet, disapproval to this interpretation is not lacking, particularly, from critics Walter Isaacson and Frank Zöllner. The first argues that the globe, not respecting the laws of optics, is not consistent with Leonardo’s studies and rigor. Indeed, it would be anomalous for an artist as precise and meticulous as Leonardo to just ignore those laws. On the other hand, Zöllner points out how the work is actually more likely to have been painted by a Leonardo’s pupil, not by the artist himself. Another negative critique has been moved by scholar Michael Daley. The expert claims that the posture of Christ does not follow the innovations introduced by the Florentine artist – namely the twisting of the bust and face. Moreover, basing his argument on a copy of the original work of the XVII century by Wenceslaus Hollar, he suggests that in the original painting the sphere respects the optical deflections. Nevertheless, as disapproval and negative critiques are never lacking, the majority of experts have argued that Salvator Mundi is indeed Leonardo’s painting.

Even with the continuous analyses and examinations, the absolute truth will most probably never be achieved. It is doubtless that an air of mystery will always surround this masterpiece, which will remain a fascinating enigma, like many other Leonardo’s works. Yet, it is thanks to these riddles that Leonardo’s masterpieces are globally famous and admired. The enigma and fascination that surround these works are indeed the reasons why the Tuscan artist is considered one of the greatest, if not the greatest, artist of all times.

Glossary:

Pentimento: The word pentimento is derived from the Italian ‘pentirsi’, which means to repent or change your mind. Pentimento is a change made by the artist during the process of painting. These changes are usually hidden beneath a subsequent paint layer. In some instances they become visible because the paint layer above has become transparent with time. Pentimenti (the plural) can also be detected using infra-red reflectograms (test that uses infra-red rays to analyze the less superficial layers of a painting ed.) and X-rays. They are interesting because they show the development of the artist’s design, and sometimes are helpful in attributing paintings to particular artists. (The National Gallery Glossary)

Salvator Mundi: Salvator Mundi, Latin for Saviour of the World, is the name applied to a type of image of Christ which was particularly favoured in Europe in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. In such pictures Christ is usually shown in ‘close-up’, often in the act of blessing the viewer. These iconic treatments of the subject were intended to be objects of personal devotion. (The National Gallery Glossary)

Sitography:

Alberge, Dalya. “Mystery over Christ’s Orb in $100m Leonardo Da Vinci Painting.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 18 Oct. 2017, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/201 7/oct/19/

“All’asta Il ‘Salvator Mundi’, L’ultimo Leonardo in Mani Private.” National Geographic, National Geographic, 11 Oct. 2017, www.sfgate.com/news/article/Rare-Leonardo- painting-to-stop-in-San-Francisco-12271061.php

BBC Production: “Da Vinci: The Lost Treasure.” Films Media Group, 2011, fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists

Desmarais, Charles. “Rare Leonardo Painting to Stop in San Francisco before $100 Million Auction.” SFGate, SFGate, 11 Oct. 2017, www.sfgate.com/news/article/

Matthews, Damion. “Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ Comes to San Francisco.” SFLUXE, SFLUXE, 17 Oct. 2017, sfluxe.net/leonardo-da-vinci-salvator-mundi/

Panza, Pierluigi. “Il Leonardo Ritrovato in America.” Il Leonardo Ritrovato in America, Corriere.it, 5 July 2011, www.corriere.it/cultura/11_luglio_01/

The National Gallery,www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/glossary.

RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA ©OsservArcheologiA

È consentito l'utilizzo dei contenuti previa indicazione della fonte